The Bushido code is a code of conduct that’s closely linked to the Samurai culture. It played an important role in the development of many Japanese traditions like the art of sword making and tea ceremonies. It also helped the expansion of Asian art worldwide.

The Bushido code was developed by Japanese warriors called Samurai, who spread their values throughout Japanese society. The Samurai drew their inspiration from Confucianism – a conservative belief and philosophical system that emphasises the importance of values like duty and loyalty which was adhered in various Japanese martial arts. The code consists of eight key values or principles that these warriors were expected to represent.

Origins

The word “Bushido” is derived from “bushi,” a Japanese term for warriors. The word “Samurai” translates to “those who serve.” These days Samurai simply means warrior.

The term Samurai was first used in the eighth century to refer to armed fighters who supported wealthy landowners. There was a power shift in the region at the end of the 12th century as the Kamakura Shogunate dictatorship was established. This was when leaders of the time popularised the use of Samurai and created a code of behaviour for their privileged status.

The Kamakura period came to an end towards the end of the 14th century when the Mongol invasion destabilised the regime. This led to a long period of peace and prosperity under the rulership of the Tokugawa Shogunate. The Samurai no longer needed to serve as a military force and took over civil governance instead. Overnight, the Samurai went from Japan’s version of medieval knights to government officials.

Art forms that were popular with the Samurai like rock gardens, Japanese painting, and tea ceremonies started to flourish during the Tokugawa period. An ordinance was issued in 1615 that required Samurai to not only train as warriors but to also train in politeness and civility. It was during this period that the Bushido code emerged as a code of conduct for all Japanese people, not just the Samurai. It was viewed as the epitome of refined masculinity.

The Bushido code teaches respect, appreciation for life, mercy, benevolence, and leading by example.

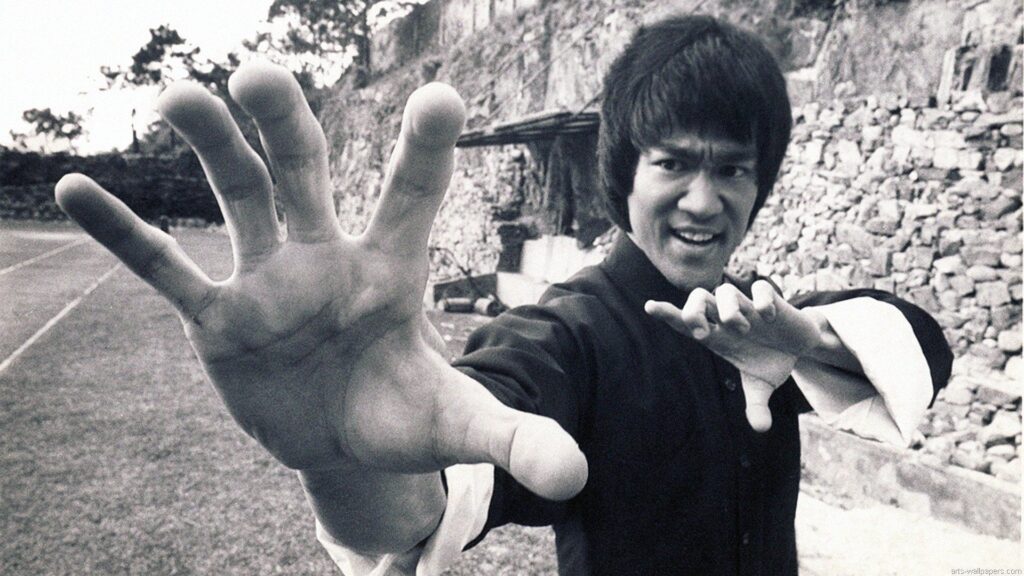

The Unlikely Samurai

Japan’s Age of Wars was a time when bloodshed was the norm and the sword was the law. A peasant boy named Hideyoshi who didn’t have a coin to his name wandered the Japanese countryside on a quest to become a warrior.

Hideyoshi was hired as a sandal-bearer by a brutal young warlord named Nobunaga. Determined to be more than a peasant, Hideyoshi worked his way up the ladder and eventually became Nobunaga’s right-hand man and protégé. He went on to become the first peasant to be the supreme ruler of Japan and unified the nation after hundreds of years of unending wars.

Hideyoshi’s story has lived on for centuries in movies, plays, video games, and novels. It’s not every day you hear of a frail peasant boy rising to become a nation’s supreme ruler. In Hideyoshi’s days, peasants could only escape a life of tedious farm work by becoming priests or warriors. Hideyoshi rose from poverty and went on to rule a nation and command hundreds of thousands of Samurai.

Hideyoshi’s tale became the ultimate rags-to-riches story in Japan. One of the things that makes his story so interesting was how different he was from other Samurai. He often looked to build alliances and make peace with his adversaries, instead of using brute force to dominate them. He never became much of a fighter despite his training, so he wisely chose to rely on his wits instead of his sword.

Peasants didn’t always have the opportunity to join the Samurai in Japan. The term originally referred to nobles who had been assigned to serve as guard members of the Imperial Court. This is where the service ethic of the Samurai was born. However, nobles eventually had difficulty keeping centralised control of Japan, forcing them to outsource duties of the Samurai like tax collecting, administration, and military protection to their former rivals. Local governors became more powerful as the Imperial Courts grew weaker until some became feudal lords called Daimyo who ruled territories independent of the Imperial Court’s central government.

A warlord named Minamoto no Yoritomo, whose heritage is traced back to the imperial family, established Japan’s first military government, starting the feudal period that spanned from 1185 to 1867. The feudal period initially brought stability to the region, but the peace didn’t last long.

Other regimes came along and the military government collapsed in 1467. This led to the Age of Wars as local warlords battled to conquer rivals and protect their domains. By the time the Age of Wars started, the term Samurai meant professional soldiers or armed government officials.

The worst of the Samurai were no better than street hooligans, while the best of them were fiercely loyal to the code of behaviour now called Bushido and their masters.

In modern times, the Samurai are a highly romanticised archetype that emerged as the most colourful central figures during one of the most tumultuous times in Japanese history. They’re Japan’s version of cowboys in the Wild West or medieval knights in Europe.

The Samurai’s role changed significantly when Hideyoshi pacified Japan by forming alliances until he became the supreme ruler. The Samurai were no longer needed as professional warriors at that point, changing their focus from martial training to arts, teaching, and spiritual development.

The Samurai were officially abolished when the public wearing of swords was banned. They finally evolved into what Hideyoshi had envisioned centuries earlier: swordless warriors who relied on their wit instead of brute force.

The Code

In an interesting twist of fate, U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt helped to popularise the Bushido code when he spoke about a new book he read called Bushido: The Soul of Japan. He bought several dozen copies of the book for his friends and family members. The book was written by Nitobe Inazo who interpreted thousand-year-old precepts for men. It went on to become an international bestseller.

The book reveals a code of conduct that emphasised benevolence, compassion, and other non-combat-related qualities as the basis of true masculinity. There are eight virtues expressed in the Bushido code:

1) Rectitude Or Justice

The virtues of Bushido refer to personal and martial rectitude (morally correct thinking or behaviour/righteousness). Rectitude or justice is the strongest virtue of the Bushido code. A Samurai describes it as ‘one’s power to decide upon a course of conduct in accordance to reason without wavering; to die when to die is right, to strike when to strike is right.’

Another Samurai explains it like this, ‘Rectitude is the bone that gives firmness and stature. Without bones, the head cannot rest on top of the spine, nor hands move, nor feet stand. So, without rectitude, neither talent nor learning can make the human frame into a Samurai.’

This Bushido virtue is still found in martial arts like Judo that are derived from Jiu-Jitsu –which was the style many Samurai trained. It’s a strong belief that you must be righteous to reach the peak of many combat systems. This righteousness is what gives the warrior the bravery to defend his home even though he knows it might be his last fight.

2) Courage

Bravery and courage are two different things in the Bushido code. It only counts courage as a virtue when it’s exercised with righteousness. Courage in the Bushido code means doing the right thing. Confucius says, ‘Perceiving what is right and doing it not reveals a lack of courage.’

3) Mercy Or Benevolence

The Bushido code required men who had the power to command others demonstrate high levels of mercy and benevolence. Sympathy, empathy, affection for others, magnanimity, pity, and love are traits of benevolence. It is the highest attribute the human soul can attain according to the Bushido code. Confucius describes benevolence as the highest requirement for leaders.

4) Politeness

It can be difficult for some to draw the line between politeness and obsequiousness. Courtesy and good manners are rooted in benevolence, and they remain important values for many Japanese people. Obsequiousness is when you’re nice to people because they’re important or want something from them. It should not be confused with politeness which is a benevolent regard for how others feel. Politeness in its purest form is a lot like love.

5) Sincerity and Honesty

According to the Bushido Code, true Samurai were not motivated by money and believed men must have disdain for money because it hinders wisdom. The children of high-ranking Samurai were taught to believe talking about money was distasteful, and that ignorance of the value of different coins used during the period was a sign of proper upbringing.

The Bushido code encourages being thrifty, not to save money but to learn how to live without much. Luxury was viewed as the greatest threat to manhood and the warrior class was required to not seek wealth.

6) Honor

The Bushido code required Samurai to be honourable and carry themselves with dignity. Samurai were raised to value the privileges and duties of their profession. The fear of disgrace hung over the head of the Samurai. Short-tempered Samurai were ridiculed for their behaviour as honour requires patience.

7) Loyalty

The Bushido code dictates warriors should be loyal to those they are indebted to. Loyalty exists among different groups of men from warriors loyal to their masters to pickpockets loyal to their leader. The code places loyalty as a major characteristic of true manhood.

8) Character And Self-Control

The Bushido code teaches that men should have an absolute moral standard that transcends logic. It prioritises knowing the difference between right and wrong and expects all men to know the difference. It also obligates men to teach their moral standards to their children by using their behaviour as an example.

One of the first goals of Samurai education was to build up the student’s character. Dialects and intelligence were viewed as less important. Intelligence was nice, but a Samurai being a man of action was more important. Hideyoshi personified the eight virtues of Bushido during his life. Like many great leaders, he had as many strengths as he had weaknesses, but by choosing benevolence over belligerence, and compassion over violence, he showcased the ageless attributes of true masculinity. He went on to become the greatest Samurai of his time despite not being able to fight as well as the average Samurai. Many of the lessons taught in the Bushido code apply to modern life.

The Modern Day Samurai

The days of the Samurai have long passed, but that doesn’t mean you can’t be a modern-day Samurai. You can even keep the kimono, but you probably want to lose the sword depending on where you live. Some of the things you can do to become a modern-day Samurai include:

- Learn At Least One Martial Art: The Bushido code expects men to be proficient in martial systems. Martial arts training stresses the virtues of the Bushido code and takes you on a journey of self-discovery that makes you the best version of yourself. You’ll also learn how to protect yourself, your friends, and family members like an honourable warrior if you’re ever forced to.

- Prioritise Being A Positive Force On Those Around You: This means sincerely wanting everyone around you to be successful in their endeavours. Be the best parent, friend, and partner you can be. Make virtues like loyalty, honesty, courage, and benevolence a significant part of who you are. You don’t have to be perfect all the time, just try to be the best you can be.

- Strengthen Your Mind And Body: This includes activities like martial arts training and strength and conditioning. Warriors should get their bodies to the best shape possible so they can perform at their best if they ever need to use their martial arts training. Your mind should be just as strong as your body since self-control is a virtue of the Bushido code. A Samurai doesn’t let their emotions lead them into making poor decisions.

You may also like: